The fantastic sculptures that surprise walkers of the narrow, twisting pedestrian streets that radiate upward from the bottom of the basin to the forts and statues on the rim are a whimsical menagerie commissioned by the International Cervantino Festival. I found them captivating and decided to photograpIIIIIIIIIIh them. You'll find them among the photos that follow. Leonora Carrington, the sculptor, was born in England and Lived in Mexico. Her second husband Emerico Weisz (nickname “Chiki”), born in Hungary 1911, was a photographer and the darkroom manager for Robert Capa during the Spanish Civil War.

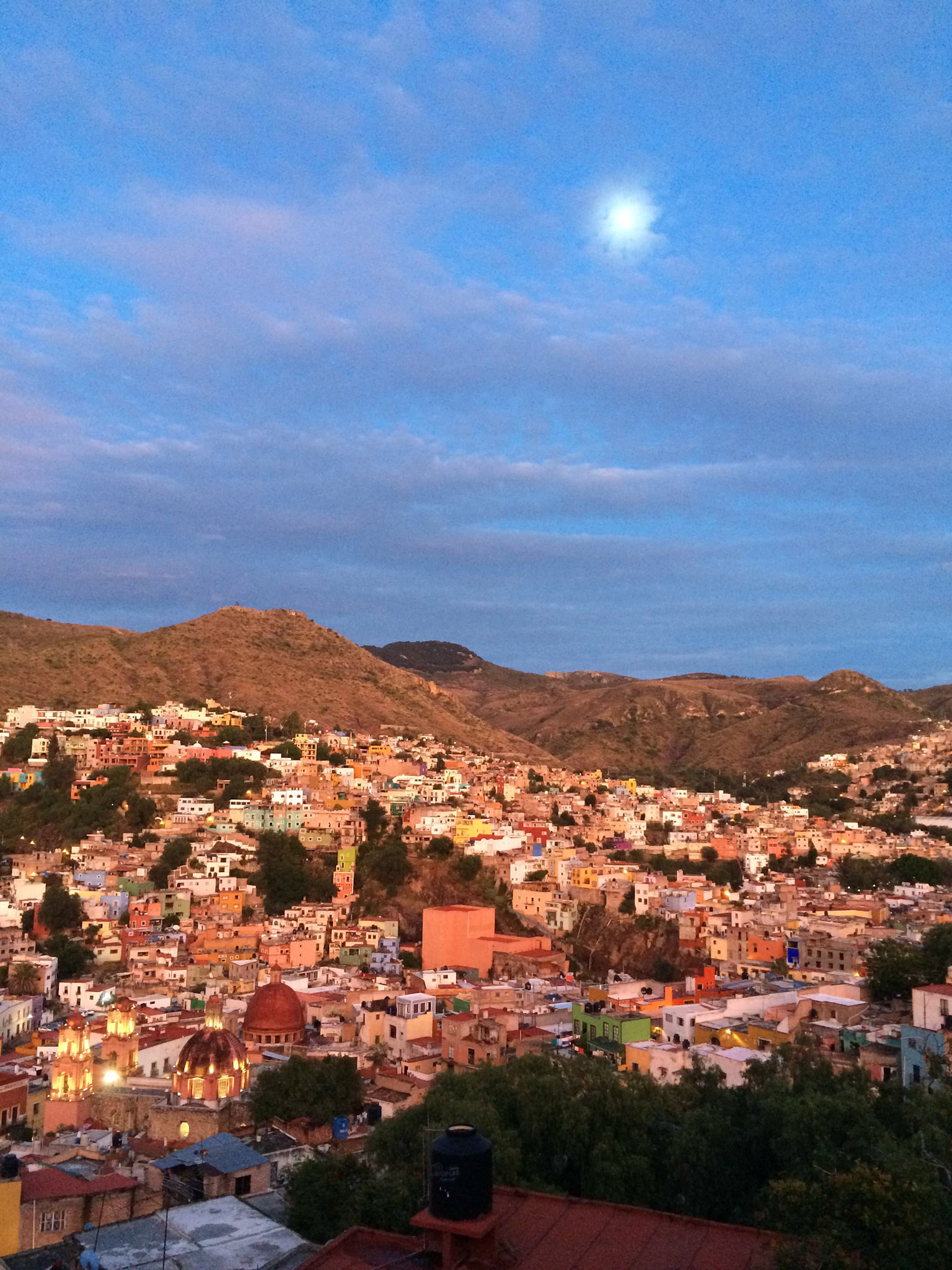

Guanajuato sounded fascinating when we were planning our trip. We really didn't appreciate how much we would think of this place afterward. It's bright in our memories. I find it more so as I write about it now (2018.07.13)—nearly three years later and almost a year after a 42-day trip in Europe.

This city has is a lot going for it:

• Histories (the long tapestry of indigenous and colonial politics);

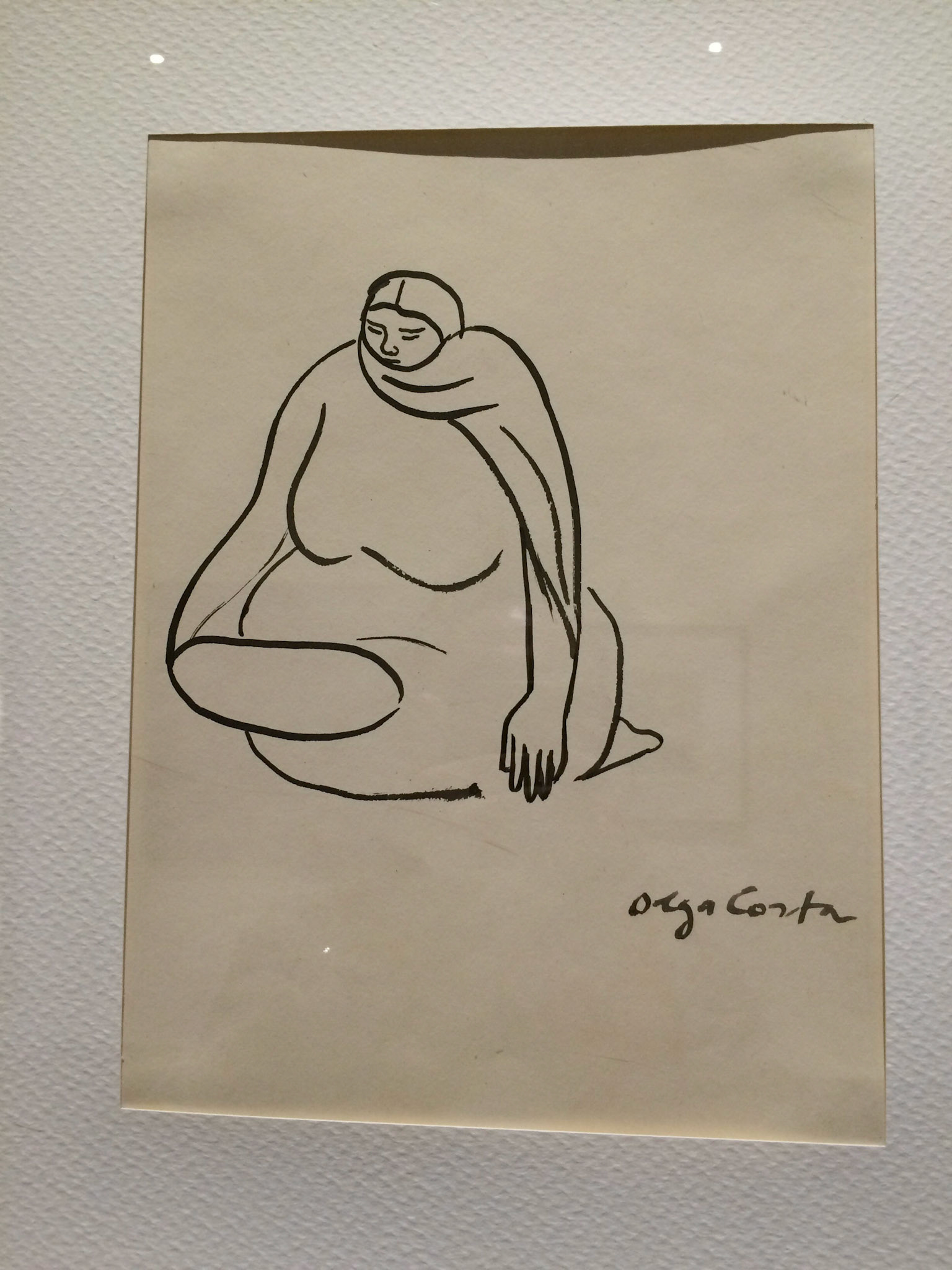

• Art

• Cuisine

• Geology

• Geography

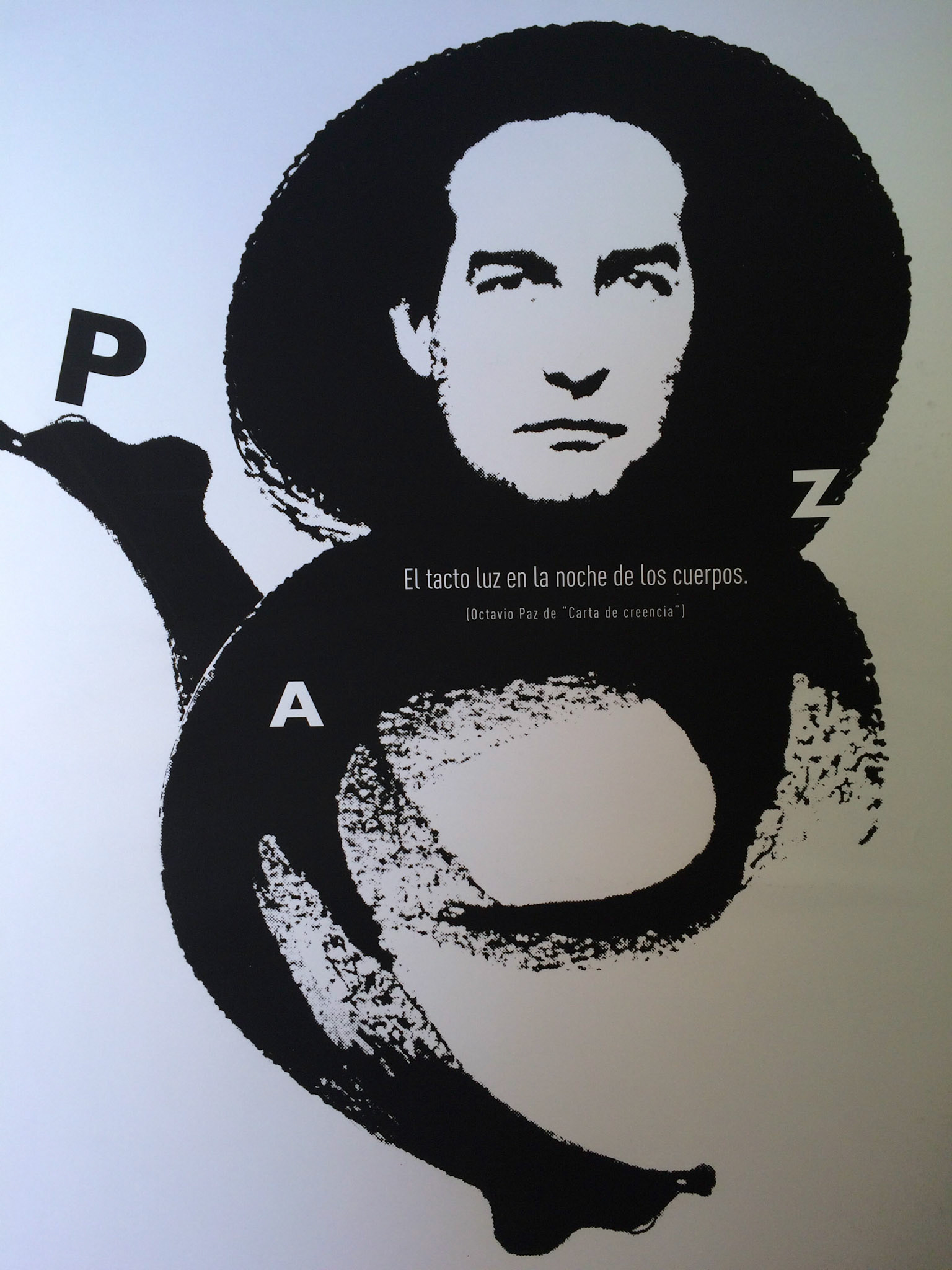

• Literature

• Craft

But its foundation is on precious ores. The city-in-a-bowl sits on top of its own creation and the national creation in a surreal way. The mountain below the city—and those surrounding it—are honeycombed with mine shafts and tunnels. The incredible veins of silver that helped finance Spain's conquests were found around 1750. Serious mining began in 1774—before there was a United States of America.

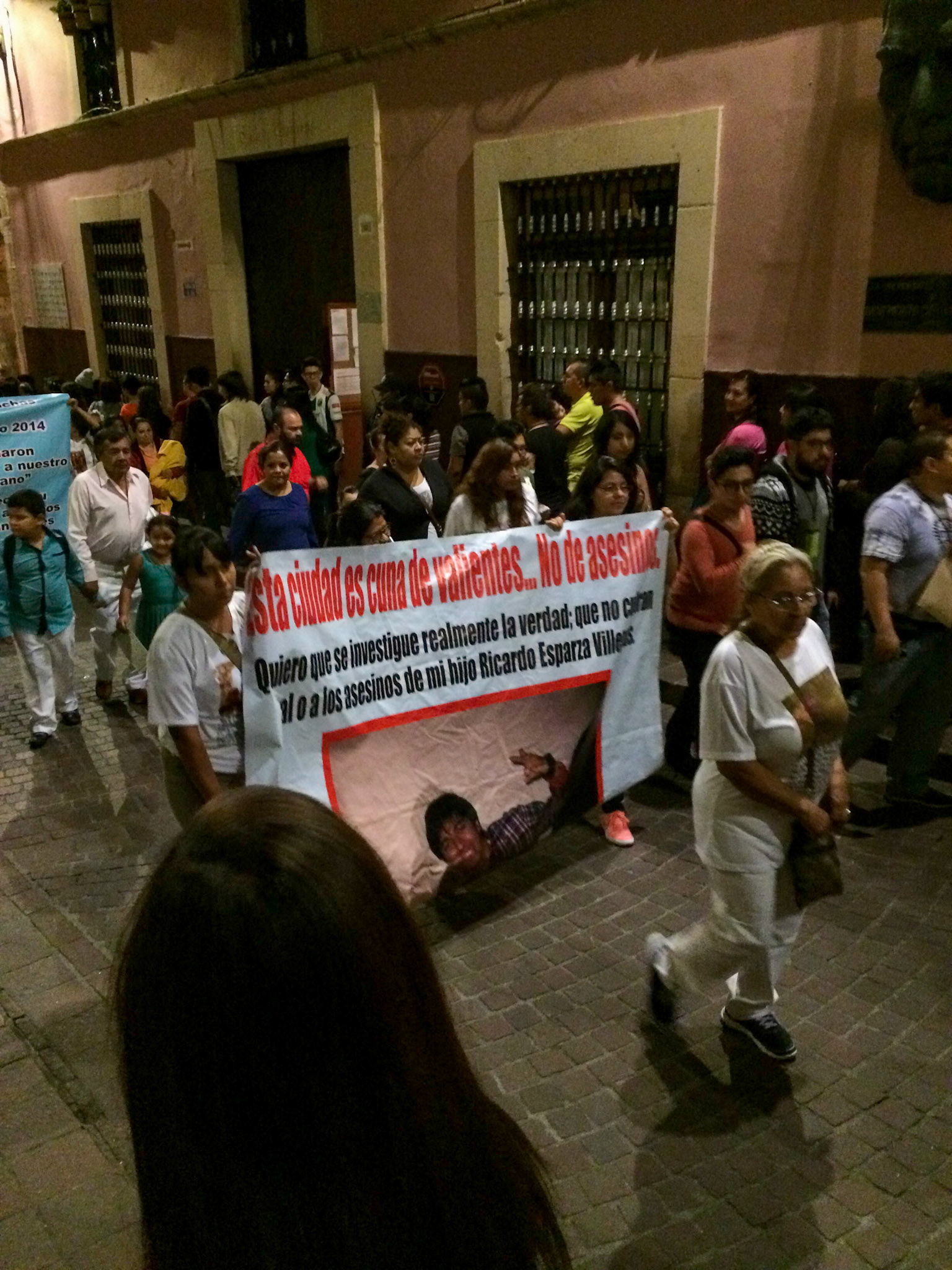

The old city certainly wears its history, from the slavery and exploitation of the indigenous people in the mines beneath land stolen from them to the geographically transposed Spanish aristocracy and other exploiters, including the Church who shaped modern Mexico.

I was unsurprising to learn that the successful revolution under Hidalgo got started here and in adjacent communities. On the rim of the city on one side is the Spanish fort. Across the bowl of the city on the higher rim is a monumental statue of El Papila—the peasant hero of the revolution. He was a crippled miner.

For centuries, precious metals were tortured from the earth. At its peak, the La Valenciana Mine produced nearly a third of the worlds' silver annually. Over 3000 slaves mined the ever-deeper and thinner seams for every ounce of ore that could be gotten. The Church anointed it all and reaped riches for its own part of the aristocracy while converting (or killing) the natives. As usual, beautiful cathedrals were built from some of the stolen wealth.

As the revolution was brewing, the old guard became for repressive and defensive. When they finally felt the pending fury of the crowd in the princely city of Guanajuato, they decided to the hole up in the defensible and easily-fortified city grain warehouse, El Alhondiga de Granadita. The local upper classes moved themselves and their treasures into their fortification. They had food, water, and the soldiers to defend the place from a relatively unarmed rabble. They'd sent for help and expected it soon.

The weak spot in their plan was the building's only notable weakness—it's wooden doors. A crippled miner known as El Pipila (the turkey) because of his gait strapped a large stone on his back as a shield and carried a burning torch and a bucket of hot tar to the base of the doors. He set a fire that could not be fought from inside and that created a cover of smoke for an assault when the doors weakened. It was the first real victory of the insurrection that would free Mexico from Spain.

Unfortunately, the revolution mostly resulted in the Mexican branch of the Spanish aristocracy keeping the game the same. That revolution remained to be done.

We learned much of this after getting there. My prep reading before the trip was neither deep nor broad because I hardly knew where to begin. Spending our first week in Guadalajara had helped, But this is an important place in Mexican history. It's important in the moment too—a center of government, commerce, and education. Around the end of October, the city hosts the world's premier Cervantes festival. We caught the dying days of it and found the general level of "party hardy" to be a curious remembrance of the author.

Come to think of it, it's an unlikely bookend to the love of all things Washington Irving in Spain; there are plaques, streets, and highways named for him. We stayed in a hotel that he stayed at. I wonder what he thought of the pizza.

We'd lucked out getting a place to stay at all when we called around not knowing about the festival. By simple accident, Linny phoned just as a someone else canceled. Guanajuato was a jumping place even when we left after the festival, and it would be great to go back when it's calmer. But it was good.

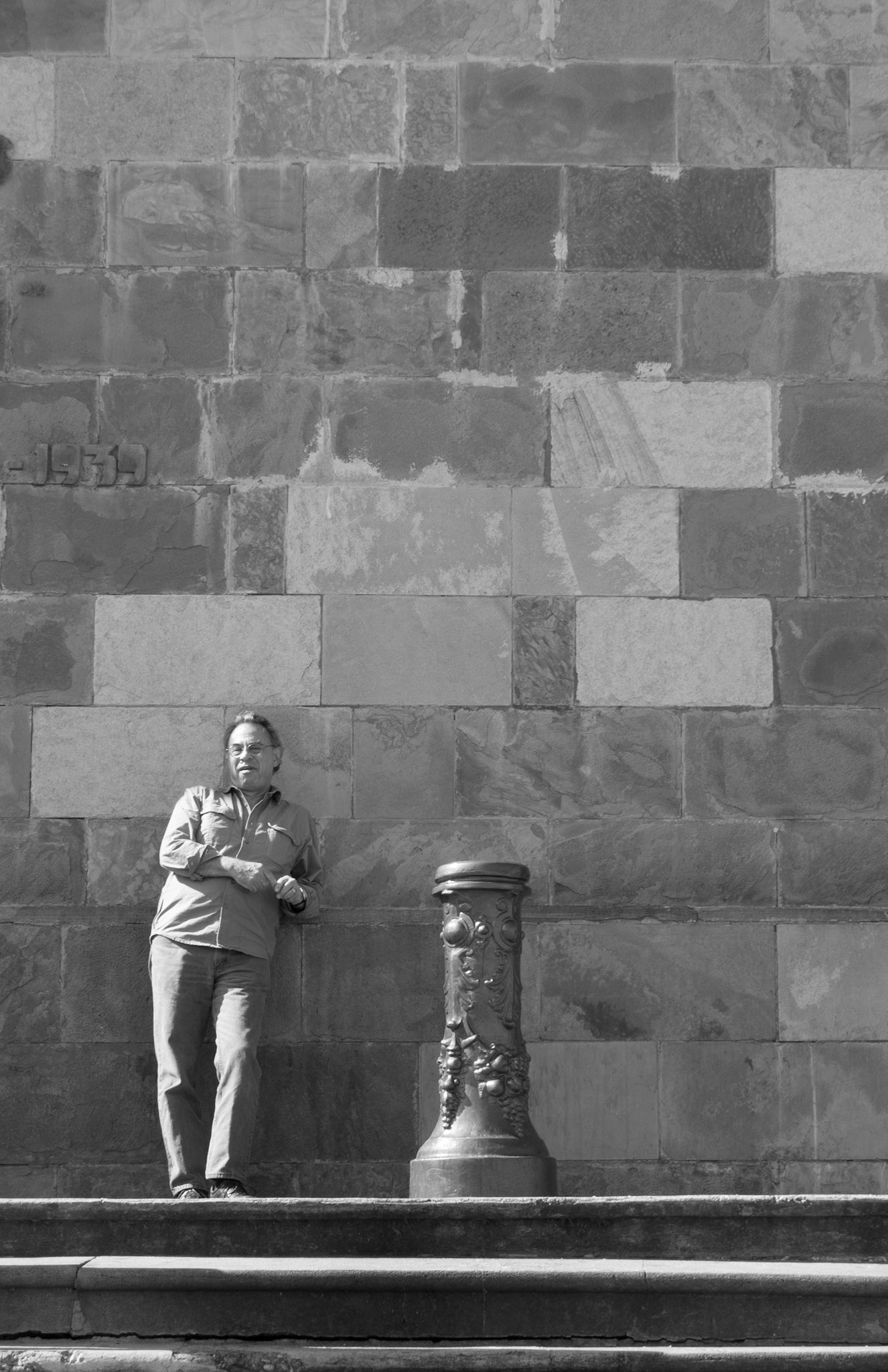

There are excellent museums, and the city is its own. The shaded squares. The market. The public art. And did I mention that there are only a couple of streets with traffic. It is a demanding pedestrian city. Steep hills, lots of stairs, incredible colors. Interesting food. Great views. Warm people.

We stayed two houses below the rim close to the monumental statue of Pipila and the incline that stops only at the top and bottom of the long hill. We walked it at all hours and enjoyed the changes and even the challenges of serious stairs work. About 20 minutes up or 2 down (after a cab ride that might be 15). So we climbed and enjoyed it. The reward at the top our climb was the exceptional B&B we came upon by chance: Casa Zuniga. If you don't feel like going anywhere, you'll be happy right there. At the bottom is the concentrated city of grand public buildings and churches, an important university, shops, restaurants, plazas, and offices. Without the cars.